Centres of learning have a long history. Presently, institutions of learning, particularly universities, remain part of the European heritage that has its origin in the Medieval Christian tradition (Ruegg, 1992). Predating the European institutions were institutions in Asia (Verger, 2003) with their origins in Islamic or Buddhist traditions, but these have had little or no influence in universities today.

The universities we attend today are modelled around this European tradition. Originally universities were divided into four or five faculties: Liberal Arts, Law, Medicine, Theology or Philosophy. The Liberal Arts subjects were mandatory for all learners before furthering their studies in Law, Medicine, Theology or Philosophy.

The teaching and learning strategies that developed in these institutions naturally supported the type of subjects taught, and were largely lecture and debate driven. The resulting student was able to regurgitate from memory, discuss and debate abstract notions, identify theoretical frameworks and write extensively on matters pertaining to their specialization. This was their output, supported and nurtured by the university’s measures of excellence — an environment that favoured such output.

Vocational types of disciplines such as architecture, fine arts, business, etc. were trades or crafts not part of the curriculum of these institutions of learning. They were considered unworthy of inclusion and were associated with a lower social class.

The teaching and learning strategies of vocational institutions revolved around the master and apprentice model. Students would learn a trade or skill in the work environment with a mentor or significant other guiding and demonstrating the correct way of completing a task. There were discussions, surely, but unlike universities, the emphasis was not on talking or writing but rather in doing. The proof of expertise in these disciplines were in the creations. Today “creating” has replaced “evaluation” in the revised version of Bloom’s Taxonomy — a classification system used to define and distinguish different levels of human cognition i.e., thinking, learning, and understanding.”

At the turn of the 21st century with the rise of the industrial revolution, Walter Gropius established the Bauhaus School and sought to bring together masters of form (artists) and masters of works (craftsmen) under one roof. The idea was to integrate traditional vocational disciplines such as architecture, design, product design, photography, and textiles etc. in one school where prototypes of designs were created in the workshop under the supervision of the master craftsman. The school went on to showcase its importance in ideas and innovation. Its legacy would influence many other schools, polytechnics, colleges, and universities around the world for years to come. The importance of the creative disciplines to everyday life and commerce was underscored.

Today these traditionally vocational/creative disciplines are readily offered in universities. It is not only reflective of their popularity but also arguably their importance in society and industry. However, the intention underpinning the inclusion, I suspect, was one based on a more practical concern, a concern that relates to the institutions’ bottom lines.

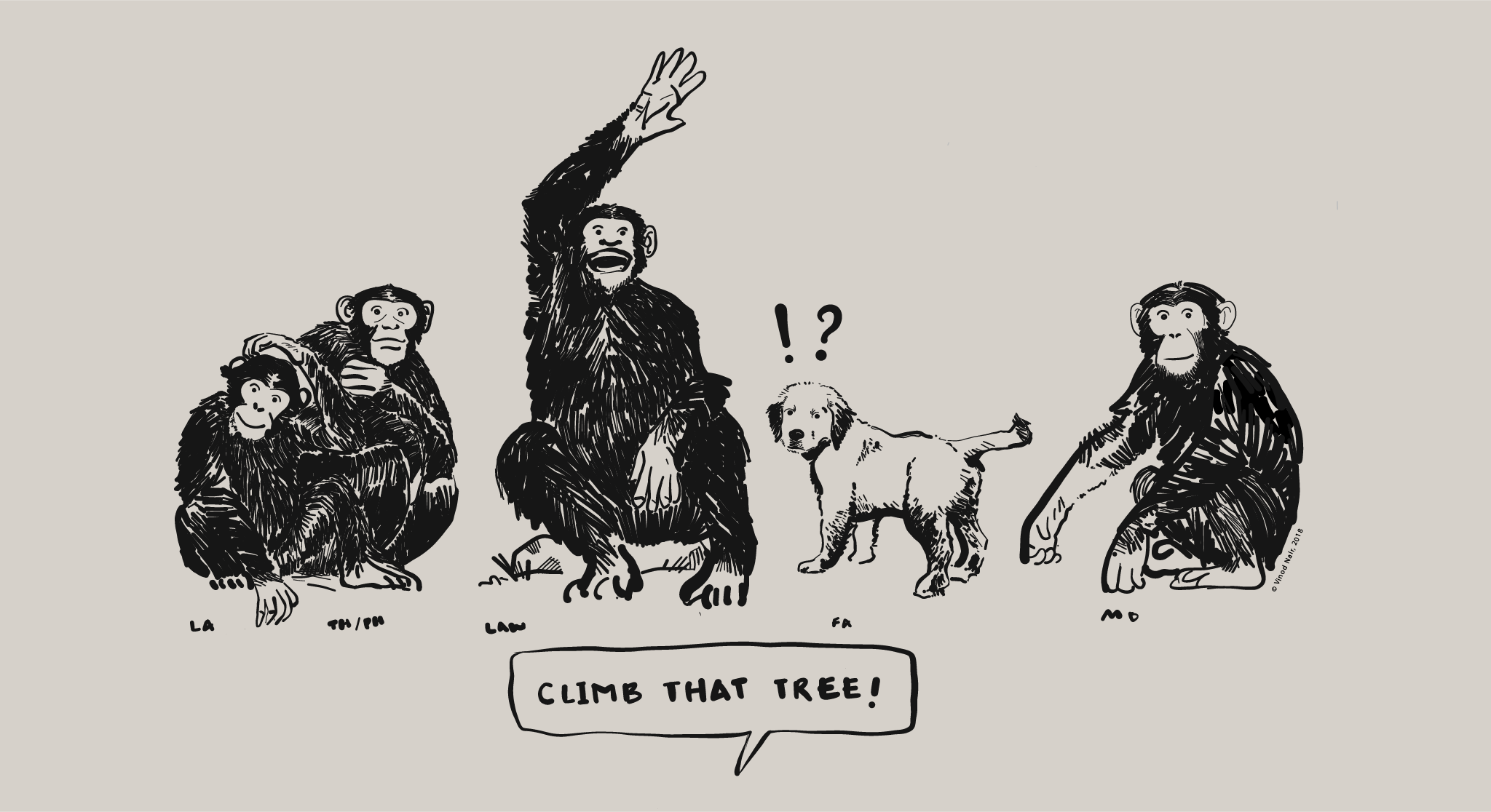

With the inclusion of these ‘vocational’ disciplines in universities, the method of teaching and learning shifted from a more ‘active’ master apprenticeship model that focused on making and doing to a more ‘passive’ lecture and debate driven framework that more closely aligned with the traditional university courses. However, without the acknowledgment and recognition in universities of the artworks, exhibitions, artefacts, photographs, commissioned works, software applications etc. as fundamental research and intellectual output, the system within universities has tended to hinder the growth of these disciplines and those tasked to administer or facilitate them in the universities. The measure of excellence in universities has grown around the traditional faculties of Liberal Arts, Law, Medicine, Theology and Philosophy, whereby the output continues in the form of writing as evidence of achievement and not in the creation of something tangible.

With the measure as such, the motivation for lecturers and students by default in classrooms tends to be skewed toward output that caters to the universities’ often rigid requirements, which does not embrace alternative means of expression. Therefore, an article in a peer reviewed journal is thought of more highly than the creation of a typeface, or a piece of furniture that addresses a real-life problem.

Often, as a facilitator in a creative discipline, in my quiet moments of reflection, I question the volition underpinning my actions. Are they to benefit the discipline and its participants or the institution’s measure of excellence? Presently I am of the view that teaching creative disciplines within the traditional university framework, with its approach in teaching and learning, and the manner of its assessment to be limiting and not in keeping with the nature of the discipline and its unbounded spirit.

The creative disciplines thrive on an iterative process that utilizes repeated failure that often also leads to unintended but valid outcomes. These kinds of outcomes are process-driven but are limited within an outcome-based system and philosophy to become “fundamentally behavioural, linear, instrumental, and lead to a loss, rather than an enhancement, of freedom for both teacher and pupil.” (Kelly, 2010. p. 71). While I have never taught in a system that emphasizes process as opposed to outcome, in theory what is espoused in a process-based curriculum philosophy seems a lot more conducive to creative-based disciplines because process is emphasised more than the outcome.

Assessments offer another area of concern in which the use of percentile or quantifiable means tends to denote a level of accuracy that does not exist in creative disciplines, “given the importance of qualitative enquiry, experiential learning, inter-subjective dialogue and creative practice in arts education, it is surprising, and seemingly inconsistent that for assessment, quantitative modes are prioritised” (Danvers, 2006). The rigour of the assessment processes in these institutions of higher learning are often meticulous and beyond reproach. The question becomes one of suitability of the type of assessment — quantitative vs. qualitative.

Perhaps I’m a little too jaded and my just-mentioned views are not an accurate representation of the reality and the progress made to cater to the creative fields in universities. Nevertheless, it is a view I hold presently based on my experience thus far and I believe there is some validity to it.

The areas of pedagogy, curriculum perspective, and assessment in universities cater to traditional faculties as described above. With the inclusion of creative disciplines, the measures used for excellence for the traditional faculties, are imposed on a field of study that cannot, and should not be measured in the same way. Thus, the questions become: are creative disciplines a good match for universities and their traditional measures for excellence? Does the university adequately recognize the tangible outputs and processes of the lecturers and or students as fundamental research? Presently, it is my view that it does not. As long as this continues creative schools, programmes, lecturers and students within universities would be measured, weighed and found wanting.

References

Danvers, J. (2006). Qualitative rather than quantitative: The Assessment of Arts Education. Network Magazine. Retrieved from http://arts.brighton.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/59419/John-Danvers-article-Networks-1.pdf

Kelly A. V. (2010). The curriculum, theory and practice. (6th Edition). London: SAGE Publications Limited.

Rüegg, Walter (1992). A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. XIX–XX

Verger, Jacques (2003). “Patterns”, in: Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de (ed.): A History of the University in Europe. Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–76 (35)