In 2000, I returned to Malaysia after studying and working abroad for about 10 years. I studied Applied Arts (Commercial Art) and majored in photography. Upon graduation I co-founded a design agency and became a freelance photographer for international magazines and advertising agencies.

When I returned, I found Malaysia was a very different country from the one I had left in 1990. My friends had become visibly more religious (in attire and in speech); people seemed a lot more polarised and divided — as reflected in the public school system; and the city in which I lived had infrastructurally and architecturally ‘developed’ to a point where some areas were no longer recognisable and others gentrified. In addition, Malaysia had become a hotbed of political activism.

While I was away, I had followed events through the BBC News channel, so I was well aware of the agitations in September of 1998 — as a result of the sacking of Anwar Ibrahim — which had preceded the activism that I noticed when I arrived in 2000. Much of the embers of the 1998 incident were still present. Just as all roads led to Putrajaya, most of the causes of the underlying problems confronting the citizenry at the time, in the view of some, also led to Putrajaya (the administrative capital of Malaysia).

In this atmosphere, among the many civil activists, was Fahmi Reza. Fahmi, just like me, had recently returned to Malaysia in 2000. He had been on a 3-year scholarship in the United States, and upon returning, unlike me, he had no intention of practising what he had studied and instead found his calling in graphic design, one that involved activism!

The first time I came face-to-face with an artwork created by Fahmi Reza was around 2004. Fahmi had been working with non-governmental organisations designing promotional material. The artwork in question was so brazen that I was taken aback by its boldness and the designer’s bravado. The graphic illustration was crude but the lines that made up the illustration were strong, visually arresting, and made an indelible impression. I was driving my mom’s Daihatsu and I stopped at a traffic light near the Employees Provident Fund (EPF), opposite the University Hospital, Petaling Jaya. It was night and I was the second car at the traffic signal. I was intending to get on to the federal highway to return to Bangsar where I lived. The traffic light was on the bridge crossing. While biding my time and looking around aimlessly I was immediately struck by a white poster stuck on the back of a billboard on that bridge. I was transfixed and in awe of how brazen the visual criticism in this work was and the boldness of the person behind it. It was uncannily accurate in its representation of how I perceived the police at the time, that the image was seared into my mind. At that point, I was rueing the fact that I did not have my Sony Cyber-shot DSC-S75 3.2MP digital camera with me in order to capture an image of the artwork. The signal had changed and I had to move the car but I resolved to come back and take a picture of it. The next evening, the artwork was torn up, probably by the traffic policemen who man the signal at rush hour in the morning.

During this period, I would also come across stencil graffiti about human rights and of a scornful Prime Minister Mahathir on the walls and alleyways in and around Bangsar, Kuala Lumpur. I remember this because I would have to pass these artworks on my way back from the ‘pasar malam’ (weekly night market) — these were artworks by Fahmi Reza, but back then he was anonymous. I think there were many of us who tolerated this defacement of public and private property because it was vandalism that voiced our collective angst and frustrations —especially in this then middle-class neighbourhood.

While I was working a regular wage paying job, and getting tied down by the responsibilities of adulthood and of domestic life, Fahmi was treading a path less travelled — unemployed, unmarried, and free from the moorings that anchored one to a life of (possible) mediocrity. He was weaponizing his art in ways that some of us only dream about. For wage earners like myself, by the time we reached home from our slave-like existence to a wage-paying master, we would be too burnt out to muster the energies required to pose a visible resistance to the political powers.

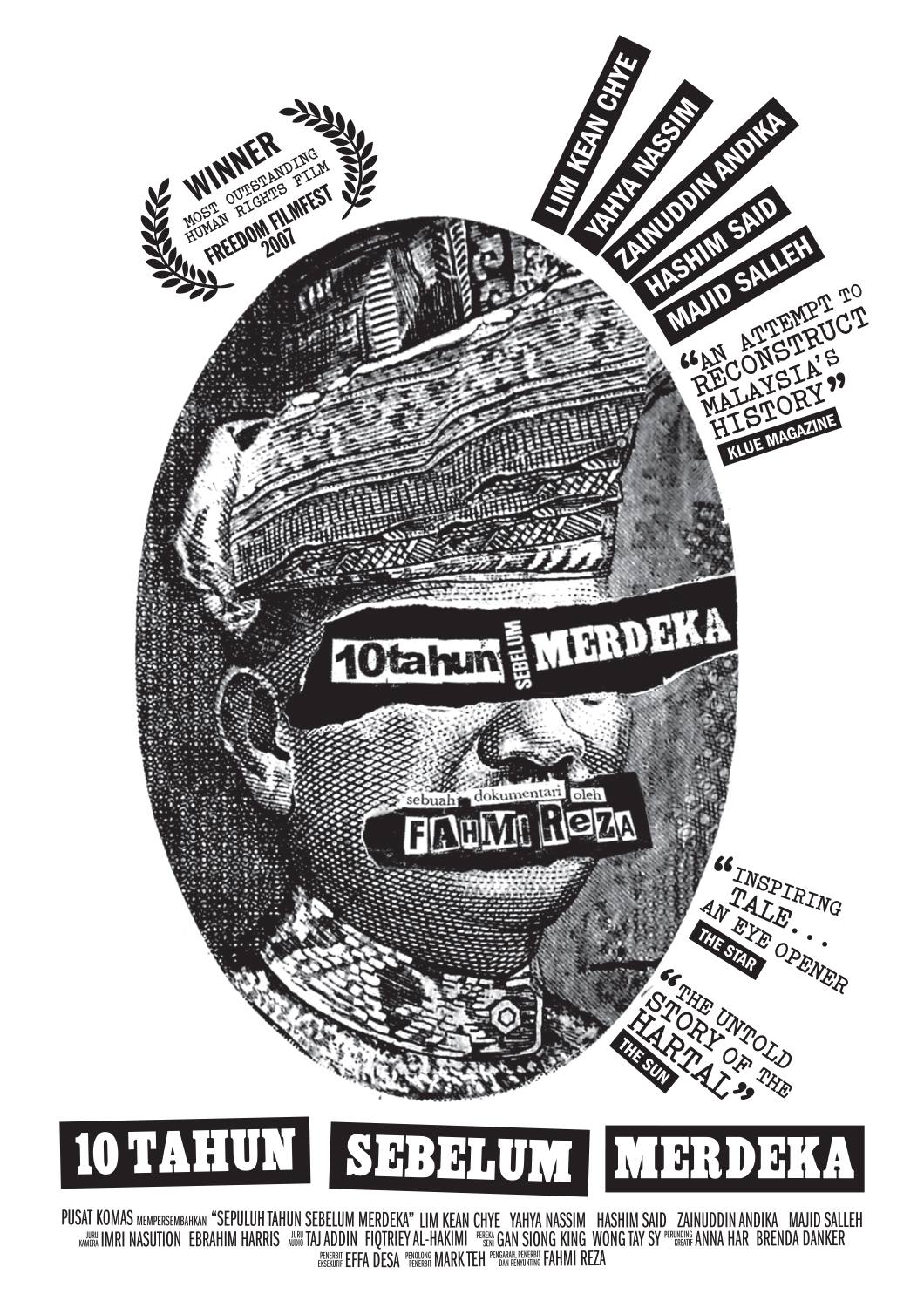

Eventually, I came to know the name of the individual behind these provocative artworks only after the award winning documentary Sepuluh Tahun Sebelum Merdeka (Ten Years Before Independence) in 2007 would come to light and the name Fahmi Reza would become publicly known and recognized. Like many, I was fascinated by a narrative that hadn’t receive much real estate in our history books but was now brought to life on screen.

During this period, I was a subscriber to Aliran magazine, which not only had some brilliant articles on the political left in Malaya but also current analysis of issues in the country. As I tended to lean left (read: political perspective) with some of my views, Fahmi’s documentary revealed a history of Malaya that related to my political sentiments.

I would later follow his many Facebook postings, and like many others, shared his artworks on my timeline. In 2014, where I was teaching at Taylor’s University, I decided to approach Fahmi Reza to exhibit his artwork at the CoDA gallery on Taylor’s campus. We met for the first time in order to discuss the possibility of the exhibition. Were it to take place, it would be the first time Fahmi would have a solo exhibition of his work. After much discussion, he would agree. The exhibition was set for the 1st of May (Labour Day) 2014. However, the endeavour hit a snag when I asked the school if they would budget RM1000 for the printing of Fahmi’s posters. While the school was agreeable as they understood the value it would bring, I was informed that as a policy, they would remain in the possession of the university. This would have been a deal breaker with Fahmi as he would not have agreed to this condition. I would then make the decision to foot the bill and fund the exhibition myself. I had invested too much time in it and I wanted to see this project through, as I believed it would be truly beneficial for our students. I would not reveal my parting of cash to the school nor to Fahmi Reza at the time, for fear that they would cancel the exhibition. The exhibition Ten Years of Visual Disobedience: 100 Political Posters by Fahmi Reza would go on to be a success.

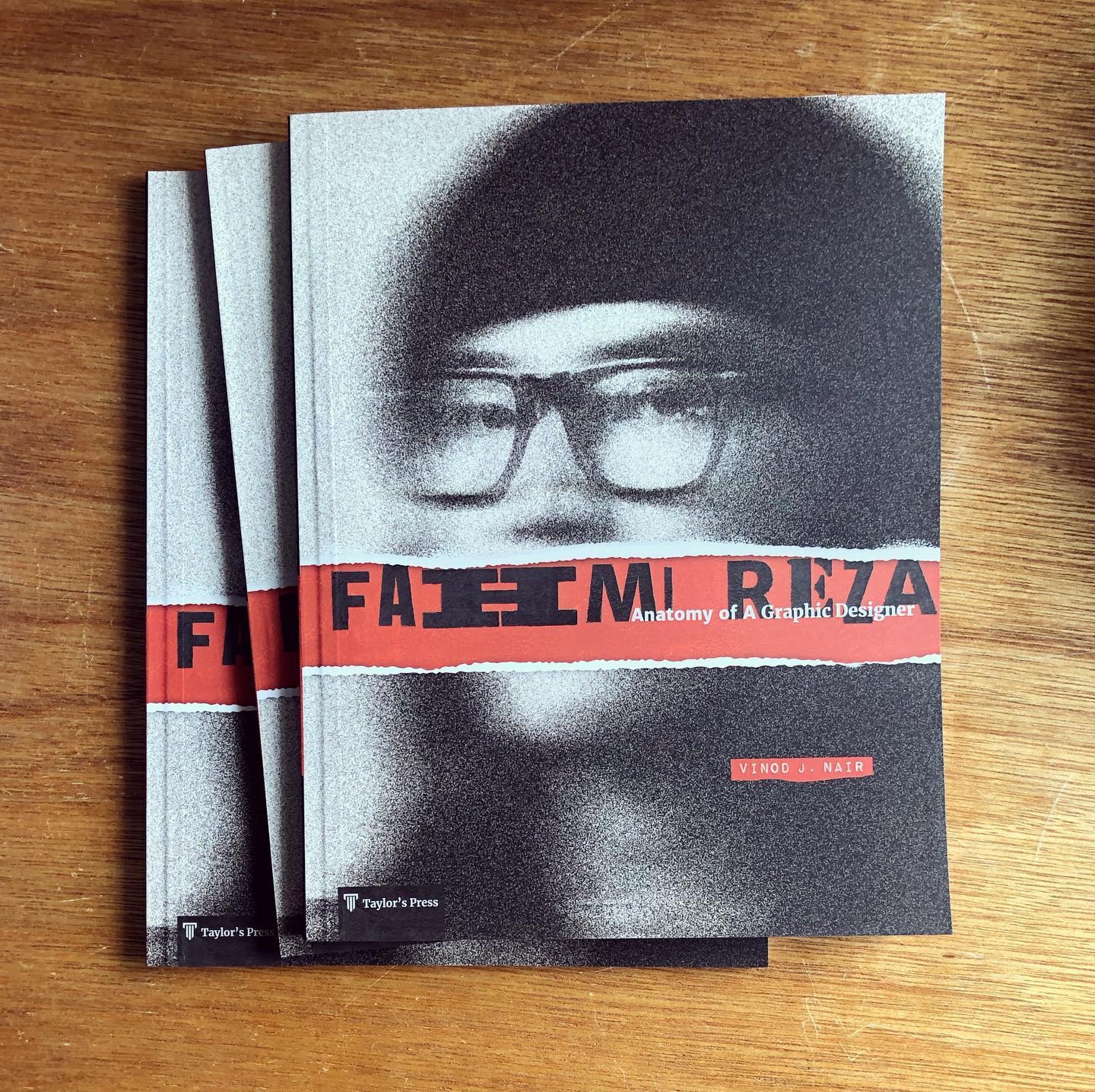

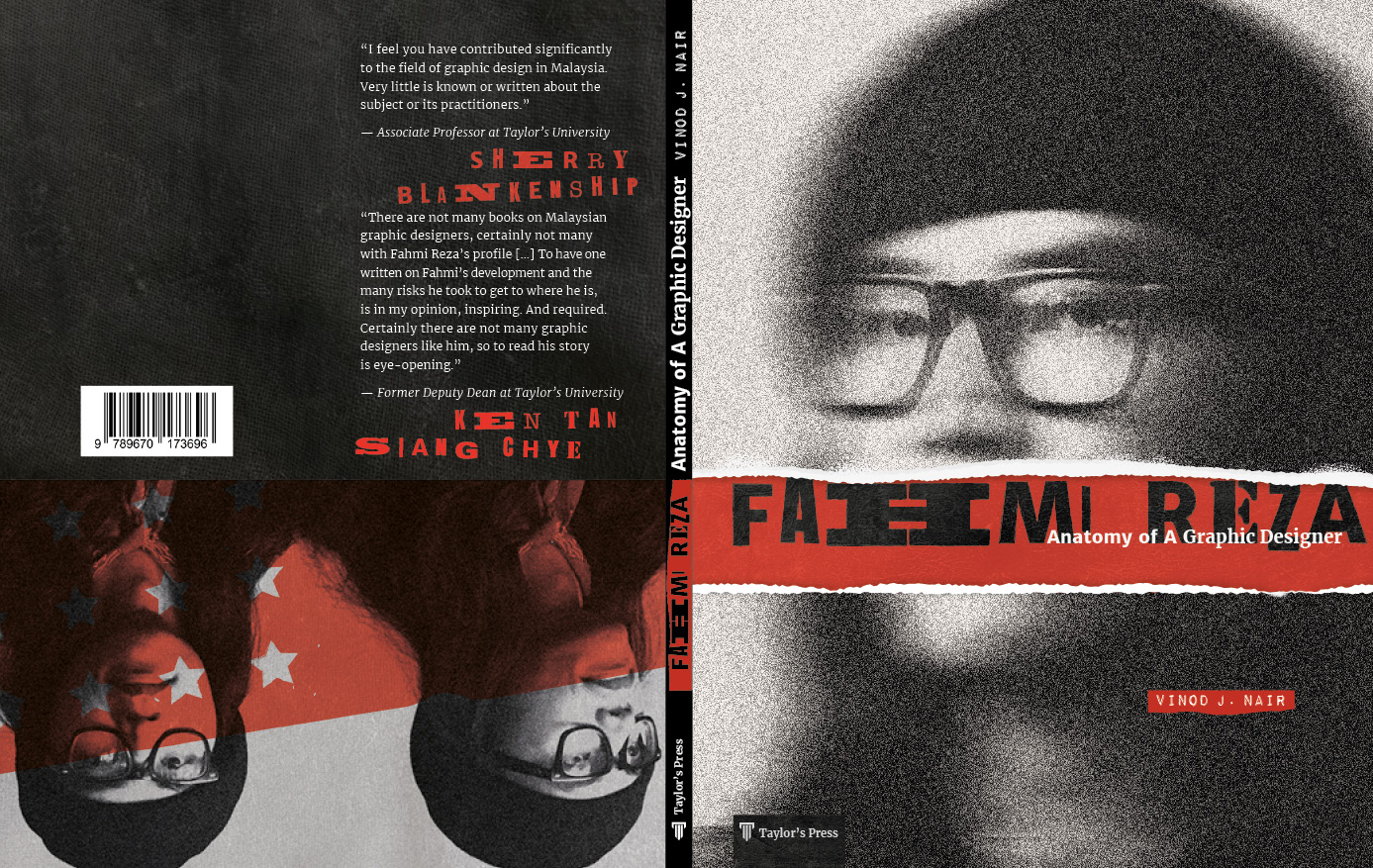

It was at this point that the idea of a book about his work began germinating in my mind. I was fueled by two ideas, the fact that there were hardly any books on local designers in Malaysia and that his body of work needed to be recorded and placed in libraries and in the hands of designers and design students. I would work on an interview instrument in 2015, I would interview Fahmi in 2017 and I would ultimately publish the work in 2020. It took that long not only because of my workload at the university but also my limited experience as a writer/biographer. I had help along the way from my colleagues (Assoc. Professor Sherry Blankenship and Dr. Yip Jinchi) in the production of this writing and to them I will always owe a depth of gratitude. This book is probably the first of its kind in Malaysia, as far as I know.

My ambition with this project does not end with Fahmi Reza. The original idea in 2015 — when designing the interview instrument — was to produce a book chronicling the journeys of five (or more) people involved in creative fields in Malaysia: lecturers, designers, and the like. From this idea, the “The Anatomy Series” was born. The success of this idea is dependent on how well the book “Fahmi Reza: Anatomy of A Graphic Designer” does. To purchase this book you may contact: TaylorsPress@taylors.edu.my or SitiRuhaida.Rahim@taylors.edu.my

For The Anatomy Series to be a real success, it also needs participation and collaboration (and much sacrifice) from other academics, students, and designers through subsequent interviews of local creatives. I also hope that students find locally significant topic areas to research and to write their dissertations. The responsibility to put forward a representative narrative from South Asia and South East Asia is up to everyone in the design field that lives and plies their trade in this region. I hope in the future, when an individual Googles “graphic designers” (or the like), the results would include names of noteworthy designers from the East. To this end, I hope I have begun to get the ball rolling with my modest contribution.